Chris Lincoln, a former recruited athlete and dean’s list student at Middlebury College, is the author of PLAYING THE GAME: Inside Athletic Recruiting in the Ivy League, published in 2004 by Nomad Press. Chris, who just appeared on Rick Wolff's WFAN radio show The Sports Edge, generously took the time recently for this exclusive Q&A with Green Alert. (In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I met several times to talk with Chris about the book and traded numerous emails with him regarding issues he wrote about.)

The Ivy League can come across a little holier-than-thou with regard to recruiting. In your research for Playing the Game, how surprised were you with what you found, and did some of the stories you heard take you aback?

I was quite surprised with what I found, and the more people I spoke with, the cleare

r it became that the problem was systemic. The irony is that the Ivy League isn’t “holier than thou” but “uglier than thou” when it comes to athletic recruiting. In terms of having athletes who are serious students, the Ivies are justifiably proud. But their recruiting system invites ugly behavior from coaches and administrators as well as from players and their parents.

r it became that the problem was systemic. The irony is that the Ivy League isn’t “holier than thou” but “uglier than thou” when it comes to athletic recruiting. In terms of having athletes who are serious students, the Ivies are justifiably proud. But their recruiting system invites ugly behavior from coaches and administrators as well as from players and their parents.Were there stories you didn't write to protect people and, if so, can you sketch one out in very general terms?

I was told things off the record that confirm my belief that the League needs to make reforms. How’s that for protecting my sources and some of the friendships I developed?

Have you heard from coaches and others in administration saying, essentially, thanks for shining a light where no light has shone before?

Yes, and it’s been very gratifying. It’s also funny because some of what I’ve heard on a positive note has been passed along in a rather hush-hush fashion or through a mutual friend. A number of coaches have told me directly that they think it’s a good book. Several have said, “I hope you mailed a copy to every Ivy president, so they can find out what’s really going on.” I’ve gotten a few calls from Ivy athletic directors, complimenting me. One said he thought I’d written a good book but not to quote him on that because “it’s too controversial.” To me, that captures the essence of the problem. People fear for their jobs, even high profile administrators who know the system is flawed, so they have to watch what they say. One of the best calls I got was from former Dartmouth AD, Seaver Peters. He’s a no-nonsense guy who tells it like it is, and when he said, “You did a great job—hit the nail right on the head,” I was very pleased. I’ve really appreciated all the support and compliments I’ve gotten from Ivy insiders.

Are you a persona non-grata on any Ivy League campuses since the book came out?

Well, I’ve said hello to Dartmouth AD Josie Harper a few times and she acts as if she doesn’t know me. I interviewed her for an hour. She knows my parents. In contrast, I chatted with (Dartmouth President) Jim Wright one day last fall, walking to a Dartmouth soccer game, and he was very pleasant. I was invited down to speak to a freshman seminar at Princeton, so I guess I’m welcome there. The book was required reading for the search committee members at Brown during their AD search a year ago. I was told that a few of the committee members from the Brown faculty and administration asked with surprise, “Is this all true?” Small-minded people in the League may be upset by what I wrote because they cannot accept criticism. They have this “how dare you!” attitude. It’s no secret the Ivy League likes to think of itself as superior, but in terms of recruiting it’s not.

Why doesn't the Ivy League recognize the letter of intent and should it?

The Council of Ivy Group Presidents cannot overcome the “pay for play” overtones of the NCAA letter of intent, which often involves an athletic scholarship for the senior high school athletes who sign the letter. This view is delusional, though, as some Ivy-bound athletes presently choose one Ivy over another based on need-based financial aid packages, which are often juicier at the better endowed schools—in particular Harvard, Princeton, and Yale. Fred Hargadon and Mike Goldberger, the former admission deans at Princeton and Brown, respectively, proposed that the Ivies adopt the letter of intent during their recent tenures, but the presidents shot them down. Karl Furstenberg, the Dartmouth admission dean, opposes the adoption of the letter of intent because he thinks “it’s exactly the wrong message for the Ivy League to send to all the high schools in America—that Larry Linebacker can hear from Dartmouth in a formal way that he’s in before Valerie Valedictorian can.” The reality, however, is that Larry Linebacker already does hear in a formal way that he’s into an Ivy League school before Valerie Valectorian, thanks to the Ivy likely letter.

You have to love the Ivy League. They talk a good game. But they want to have it both ways. They want to cloak themselves in sanctity, saying they treat athletes no differently than other students, while behind closed doors they treat athletes quite differently in the admission process. Not only can athletes learn ahead of time whether they’re going to get in, they can even get a written financial aid estimate from an Ivy school before they submit an application. How many kids from the general applicant pool can do that? It’s not sanctity, it’s hypocrisy.

What can you tell us about "likely letters?"

Likely letters are a one-way written commitment, mailed by Ivy deans of admission to high school seniors who have already made a verbal commitment to an Ivy coach to attend that Ivy school. The letter, which can be mailed at almost any date, confirms that the athletes are likely to be admitted come April. Likely letters originated because many Ivy athletes receive scholarship offers from non-Ivy schools and the League felt these potential students deserved to know where they stood before passing up a scholarship offer. I think that is a fair and reasonable thing to do. But the likely letters are also mailed to kids who do not get scholarship offers, and the abuses that stem from the likely letters and the pressure for athletes to make a verbal commitment to an Ivy coach need to be addressed. Jeff Orleans, the executive director of the Ivy League, confessed to me that he believes the NCAA letter of intent fosters greater integrity, honesty and morality than the Ivy likely letter, because “the likely letter is inviting problems the way it’s set up now.” The whole verbal commitment game gets very ugly on both sides of the ball. You hear about the coaches who abuse the system, but in fairness kids and their parents abuse it, too.

The bottom line is that athletes, because they are so highly valued by all colleges, not just by Ivy League schools, undergo their own separate and accelerated admission process. I believe there’s a way for the Ivy League to acknowledge that, while they openly and honestly pursue their goal of having high principles. I have proposed that they institute a letter of Ivy intent with a common signing date. By placing the emphasis on the word Ivy, the inherent message would be clear and forceful: athletes who signed it would be intent on pursuing an excellent education while playing their sport for passion, not for a scholarship.

Ivy coaches always talk about "no scholarships." Opposing coaches scoff and suggest that the "rich" Ivy schools are able to level out the field with their ability to give out lucrative financial aid. Who is right?

Financial aid in the Ivy League is need-based. There are no merit scholarships of any kind—athletic, academic, artistic. Schools within the League have different need-based financial aid policies, however, and these can, and do, affect how generous an aid package will be. Princeton eliminated student loans in the late 1990’s. Following that lead, Yale and Harvard have increased their grants as well, especially for students from low-income households. For an athlete who qualifies for a lot of need-based aid, the lack of any loans could save him or her $20,000 to $30,000 over four years (or even more, depending on how much grant-in-aid funds were available at another Ivy school in the recruiting battle). Everyone in the League acknowledges that the wealthier schools have an advantage.

What you hear from some coaches is that some Ivies will beef up an aid package for an athlete. Penn is reputed to give their football players a lot of financial aid. One football player who was being recruited by Dartmouth a few years ago received a full-ride offer from a scholarship school. Dartmouth could not match it, under its need-based guidelines. The difference was about $10,000. But according to the Dartmouth coach who told me the scenario, Penn did match the full-ride offer. This is impossible to prove one way or the other. You’re not going to get access to financial records like that. So the rumors and accusations will continue.

Can you envision a day when the Ivies actually give out athletic scholarships in a manner similar to the Patriot League? (Patriot League coaches suggest it raises the academic profile of the kids they are recruiting, allowing them to compete with the Ivies for the best and the brightest.)

No, this will never happen. Simply on economic terms, it’s a staggering sum of money to fund scholarships for 30-plus teams—over $250 million a year. And if you choose to give scholarships to players on just a few Ivy teams on these campuses, say to men’s basketball and men’s hockey, then you’re headed down a very slippery slope. Ivy principles aren’t going to allow that, ever. Finally, on philosophical terms, it’s hardly egalitarian to give a full-ride to a kid whose family can afford the full price of tuition when there are so many highly qualified students out there who need financial aid to attend an Ivy institution.

It’s easy to see why scholarships in the Patriot League are luring bright students who are good players away from the Ivy League, though. Skyrocketing tuition costs are threatening to eliminate the middle-class kid from Ivy rosters altogether. “Middle class families get screwed,” one Ivy coach told me. “They don’t qualify for enough aid, and yet they don’t earn enough money to afford $40,000 a year.” If you’re wealthy, you’re fine. If you’re low-income, your need-based package can amount to a full-ride, or close to it. But if you’re a middle-class kid and it’s a choice between a full-ride to a very good school and getting hit with $20,000 or more in student loans, on top of the burden your family will assume for four years, it’s easy to accept that scholarship. That’s why Ivy teams are increasingly composed of rich kids and poor kids and fewer and fewer middle-class kids. This trend will only get worse. Ultimately, I think it will make it harder for the Ivies to compete successfully outside their own league. And watch the Ivy basketball coaches leave for other jobs in the next few years. I’m told a few are already looking.

In your opinion, would the Ivy principles be compromised by giving scholarships to academica

lly qualified student-athletes, and is there a right way to do it?

lly qualified student-athletes, and is there a right way to do it?I see no need to give merit scholarships of any kind—athletic, academic, artistic—to any students in the Ivy League. I admire and applaud the League’s commitment to need-based financial aid. It’s absolutely the right way to go. If athletic standards begin to fall, the League can join Division III. (Do I hear a chorus opposing this option?)

The slide in Dartmouth's football fortunes coincided with the now infamous and well-documented letter written by the Dartmouth admissions director damning the culture of the sport and those who play it. Many people believe the admissions situation contributed significantly to the downturn in Dartmouth football's fortunes. Do you?

Yes, I do. But the person responsible for altering the Dartmouth football admission landscape was not Karl Furstenberg, the author of the damning letter to Swarthmore. It was the late Dartmouth president, James O. Freedman. To his credit, President Freedman was open about his mission to raise the academic profile of the Dartmouth student body and to create a more intellectually driven Dartmouth community (“the eggheads” as one Big Green football coach called them). Karl Furstenberg was hired by Freedman as a simpatico admission dean to help execute Freedman's over-arching goal to raise the academic bar and admit a more academically gifted student body. This was a seismic shift in overall school policy, not Furstenberg’s private agenda, and it was not simply an athletic admit issue, though it did affect the football program.

Ironically, the slide in Dartmouth’s football fortunes occurred the very same year that the Big Green enjoyed their last undefeated season, 1996. John Lyons told me he knew he was doomed that fall, just after that incredible 10-0 season, when he returned from Princeton and found Dartmouth’s new A.I. numbers on his desk. They had risen sharply, finally shifting (remember, they're based on a rolling four-year average, so it took a while to boost the school's mean AI to new heights under Freedman), and the numbers were so high that Dartmouth football was now competing for players on an equal footing with Harvard. There was no longer an A.I. band advantage for Dartmouth.

As for individual football admission decisions made within these new A.I. band parameters, Lyons and his staff were not always supported by Karl Furstenberg. But other coaches in other sports were also frustrated by the Dartmouth admission office at times. It’s part of the joy of coaching in the Ivy League. You bring forward a strong candidate for admission, with an A.I. that falls within the school’s range, place him high on your list, and then sit back and watch the kid get rejected.

Given they don't work in a vacuum, how important are the personal beliefs of the admissions director to the athletic fortunes of an Ivy League school?

Everyone gives Fred Hargadon, the dean of admission at Princeton, a lot of credit for Princeton’s record-setting pace of Ivy titles between 1990 and 2003. But Princeton also has outstanding facilities, terrific financial aid, excellent coaches, and arguably the League’s best athletic director, Gary Walters. So it wasn’t just Dean Hargadon who made many Tiger teams excellent. That said, coaches at Princeton knew Hargadon was interested in their kids and supportive of them. He regularly attended (and still attends) games, matches and meets in a slew of sports. He also attended (and attends) concerts, theater performances, and other non-athletic events, telling me, “I like to let the kids know I haven’t forgotten about them after admitting them.” Several Dartmouth coaches have told me they’ve never seen Karl Furstenberg at one of their contests. Yet he rarely misses a men’s ice hockey game. Such bias would be tricky for a coach, especially when the kids you put forth on your list are getting turned down while men’s hockey is getting plenty of support. Ivy coaches do get fired for losing. Ask Dave Faucher and John Lyons.

How much of an impact does the president of the school have?

(Current Dartmouth President Jim Wright is regarded as being much friendlier to athletics than his predecessor and, perhaps coincidentally, there's a good deal of movement in Dartmouth athletics these days.)

There’s no question Jim Wright has done his share of fence-mending between the admission office and the athletic department during his tenure as president. He’s made the goals clear to both parties and has asked them to work together and communicate more effectively. ... It will be interesting to see what Columbia does with its athletic program under its current president, Lee Bollinger, who came from academic and athletic powerhouse Michigan in 2002. He’s hired a new athletic director and she’s been hiring new coaches, who say they’ve come there to win. Will the Lions begin to roar in the athletic arena? Stay tuned….

My sense from talking with Jeff Orleans, the executive director of the Ivy League, and with Jim Wright, is that the Ivy presidents all have their own individual views on athletics and as a result it’s a tough group to speak on behalf of. Each Ivy president also has bigger fish to fry, so it’s tough to get them to focus on athletics. The final problem is that Ivy presidents turn over with some frequency, so when it comes time to discuss athletic policies there is often at least one new president to bring up to speed. And he or she can have his or her own strong feelings on the subject. As a result of this turnover and lack of inside knowledge, Jeff Orleans wields a good deal of influence and power. And yet, the presidents don’t always follow his recommendations, some of which would certainly improve recruiting ethics—or the lack thereof. In a way, the issue is this: can anyone tell the presidents of these schools anything?

I've heard a few coaches say this is the time to coach at Dartmouth because the admissions director is under tremendous scrutiny. Any truth to that?

I think Jim Wright has made it very clear that he supports Karl Furstenberg as an admission dean regardless of Furstenberg’s personal views. Football isn’t the only program to have frustrations with Dartmouth admissions over the past 10 years. But that frustration is part of the Ivy admission process. Each applicant is reviewed as an individual. There are no rubber stamps of approval in the Ivies, such as occur at a University of Virginia. Do Ivy coaches have to work to get along with their admission dean? Absolutely, that’s the game within the game. But Dave Roach, who was a very successful swimming coach at Brown before serving as their AD for many years (he’s now the AD at Colgate), offered a great perspective on Ivy coaching: “The interesting thing to me about the Ivy League is if you’re a good a coach and you have a successful program, the people on the outside won’t give you credit for being a good coach. They’ll say, ‘Oh, admissions have given him everything.’ Or, ‘Financial aid is helping him.’ You’re never given credit for being a good coach. It’s always, ‘Everybody did this for you.’” Well, this works in reverse as well. A losing coach can whine that admissions didn’t do anything for him or her. Sometimes it’s true; a key player gets turned away and winds up on another Ivy roster. But there are some very successful coaches at Dartmouth who don’t get every kid they want. For instance, Jeff Cook, the men’s soccer coach, has won three Ivy titles in four years, and he’s had top recruits turned down. He’s a very good coach with the ability to spot talent and develop winning teams.

What is the Academic Index supposed to do, and does it work?

The Academic Index (A.I.) is used to determine if an athlete’s academic standing is representative of an Ivy League institution’s student body as a whole. All entering Ivy League students are assigned an A.I., which is based on a mathematical formula—two-thirds test scores, one third class rank or GPA (if the high school doesn’t rank). Each school’s “mean” A.I. is based on a rolling four year average. The trouble with the A.I. is that it cannot measure intangibles (character, drive, ambition) and it discriminates against kids who either don’t test well or lack the financial resources to enroll in expensive test-prep courses. Under current Ivy rules, football is treated on its own, while all other Ivy sports must have a combined average A.I. for incoming recruits that is within one standard deviation of the mean A.I. of the whole school.

Is there something better?

I favor having an A.I. floor, under which no athlete can be admitted. After that, I support what the late Yale president A. Bartlett Giamatti wanted to do: let each school admit the class they want to admit. The trouble is, as coaches at several Ivy schools agreed, “Nobody trusts each other in this League.” So if a school starts winning, and there’s nothing regulating the admission of athletes, it’s because admissions has opened the doors too wide. Part of me wonders if the League has made the whole A.I. as complex as it is just to keep people from trying to unravel it. Your head can start spinning when you get into it, so the tendency is to throw up your hands and say, “Okay, whatever—nothing’s simple in the Ivy league.” But ultimately the schools need to become more transparent. They need to find the right way to treat athletes, not worry that they are being treated differently. Admit it and make it an ethical process.

A lot of posters on Internet message boards try to group the Ivy schools by admissions standards. Some will put Harvard, Princeton and Yale in one group, Columbia and Dartmouth in the next, and Brown, Penn and Cornell in a third group. How accurate is that, and if it's not, can you break the schools into three groups?

When I was researching my book back in 2003-2004, everyone I asked grouped the Ivy schools into three groups: Harvard, Princeton and Yale; Dartmouth close on their heels; then Columbia, Penn, Brown and Cornell. You’d have to check the most recent issue of the college marketing bible, US News & World Report, to get the latest rankings, but in the recruiting game, the top three Ivies enjoy a distinct advantage, especially with the parents of athletes. “We lose kids to Dartmouth and Penn,” one coach told me. “We lose parents to Harvard, Princeton and Yale.” Several Ivy people commented to me (and not for attribution) that there was a big difference between the academic quality of schools like Princeton, Harvard and Yale and some of the other Ivies lower on the scale. “It’s an athletic conference,” said one of these folks, “not an academic conference. It’s a big mistake to lump these schools equally on an academic basis. But of course the weaker schools love it.” Nothing like Ivy League snobbery, eh?

There have been numerous stories around Dartmouth about athletes turned down by Dartmouth but accepted at HYP and Columbia. Is it true the Dartmouth admissions director has said there's no truth to those stories? Have you heard any of those stories and if they are true, how does it happen?

I don’t know what Dean Furstenberg has said about the truth of these stories, but I do know of cases where players were rejected by Dartmouth and wound up at other Ivies—in one case at Columbia (as an Ivy Player of the Year in men’s basketball), in another case at Harvard (as a men’s soccer captain). I also know that a men’s soccer player was turned down at Dartmouth and went on to become a first team All-American at Stanford. Last year, a recruit was turned down by Dartmouth in early decision, and he’s now playing lacrosse at Yale. I’m sure there are other cases as well. This is not unique to Dartmouth, by the way. It happens across the Ivy League. Athletes are rejected by one school only to wind up on the roster of another school. Ivy admissions has been labeled “highly selective.” It might be more accurate to call it “highly subjective,” especially in athletic recruiting. I just heard about a Yale lacrosse recruit who was flown in to New Haven and welcomed to the Eli lacrosse family—only to get a rejection letter in the mail two days later. It really makes you wonder what’s going on. How does this happen?

Is it true that at some schools, a student-athlete who fits in an AI "band" is all but guaranteed admissions by the numbers while at other schools (Dartmouth being one) a good deal more subjective criteria are taken into account and student-athletes who qualify numerically are regularly turned down?

That’s a complaint you hear from Dartmouth coaches, especially about schools lower on the Ivy totem pole, such as Brown, Cornell or Penn. But I heard it from a Cornell coach, who was critical of other schools for taking kids based on their numbers, while she had to wait for her admission office to review a recruit’s entire folder. And I know of a case at Brown where a coach was told “don’t bother” to recruit a kid based on the A.I. numbers, and the player wound up as an all-Ivy performer at Dartmouth. In football, a few Ivy coaches admitted to me that they sometimes fill higher A.I. bands with players they know will never see playing time for them. But they have to fill the bands to meet their A.I. average, so they recruit these kids. More often than not, these players quit the team—what’s known as “attrition” in the Ivy athletic lexicon. The whole numeric system is deeply flawed. There should definitely be an A.I. floor, but placing kids in bands, or having a school average A.I. for athletes, is a mistake.

If you think about it, the whole A.I. is really a double-edged sword. It eliminates kids while at the same time having a numerical basis makes it hard for the admission office to reject recruits who meet the numbers. Coaches argue, “Hey, he meets the numbers. He’s within the criteria. I’m doing what you’ve asked, why won’t you let him in?” But you can have a smart kid who tests well, yet his transcript shows he’s basically lazy—B’s in non-AP courses. He’s got a decent GPA, very good boards, so his A.I. is strong, and the coach wants him. But admissions says, “Wait a minute. This guy’s underachieving in the classroom. And he did a cursory job filling out his application, his recommendations are average, so we don’t want him.” When that happens, it pisses off the coach because the recruit’s A.I. met the criteria. But the A.I. is not meant to serve as the ultimate measure, the application is. So the system, while based on a numerical formula, is hardly cut and dried. In fact, you could say it’s even more complicated because of the A.I. and the averaging that must take place to conform to League rules.

Dartmouth is in the midst of an incredible building boom regarding athletic facilities. How important do you think facilities are to Ivy League student-athletes?

I think they’re very important to every Ivy athlete, and I also think good facilities are vital for other students who are not varsity athletes—who want to exercise, play intramurals, stay fit. It’s great to see Dartmouth making that effort across the board. Will they ever equal the facilities at Princeton? No, but at least they are putting themselves back in the game.

Your book counters but in other ways confirms some of the findings Bill Bowen published in the Game of Life and its successor. Have you heard from Bowen and what's your take on his findings now that you've dug into the Game yourself?

I have never heard from Dr. Bowen. He avoided my interview requests as I researched my book, and he hasn’t called me to chat since its publication (laughs). I’m not a statistician and cannot address all his findings on that level. Others who are more qualified than I am have questioned his methodology and many of his conclusions. Perhaps the best description of Bowen’s statistical analysis of the academic underperformance of Ivy League athletes is that he has “exaggerated small differences.” For instance, the underperformance he cites of Princeton athletes (based on their test scores and grades) amounts on average to a 3.2 GPA when comparably qualified students earn a 3.6—or, a B+ instead of an A-. I think it’s pretty clear from what’s he’s written that he carries a deep prejudice against athletes. In a previous book he wrote with then-Harvard president Derek Bok, The Shape of the River, about minority admissions, Bowen makes the exact opposite argument that he makes in The Game of Life. In The Shape of the River he and Bok argue that test scores and grades alone are not accurate predictors of a minority student’s potential or merit, and should not used to determine a student’s worthiness for admission. Yet in The Game of Life those are the basis of his argument. Further, he and Bok write: “…it is not clear that students with higher grades and scores have necessarily worked harder.” The double standard is quite clear, and Bowen’s politically-correct, anti-athlete bias, is alarming. He’s feeding a stereotype which is grossly unfair.

I do agree with Bowen on one thing, however, and that is the danger of athletes at these elite schools devoting so much time to their sport and spending so much time with their teammates that they are living increasingly narrow lives in the midst of these extraordinary campuses.

What is the biggest myth about Ivy League athletics?

That all the athletes got in just because they are good at their sport. The majority of these kids are very hard working students, and many are quite talented academically, not just gifted athletically.

Are you working on anything interesting now?

I am working on a novel set on the West Bank, where I lived and worked on an Israeli settlement years ago. Much of the story is written. Now I’m doing research that will allow me to set the story in the present day. It’s a subject not unlike Ivy recruiting and athletics—in the sense that people hear a lot about the West Bank and the settlements there, but they don’t know the inside reality of what it’s actually like to live there, how settlers vary in their views, how politics and power influence even the smallest actions. Thanks to living there, I have the inside knowledge. I've got a good story and some compelling characters. Now all I need is an editor and publisher to take an interest, offer me an advance, and say, “Let’s go.”

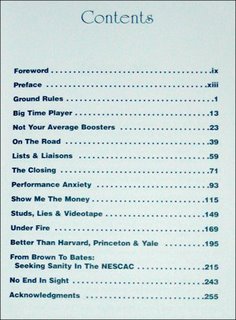

Where can people get your book?

They can order directly from the publisher, Nomad Press, by visiting their website, or by calling 802-649-1995. Or they can go to amazon.com and support billionaire Princeton alum Jeff Bezos, who also sells used copies of the book that return no royalty payment to the author. I recommend Nomad. Thanks for asking.

No comments:

Post a Comment